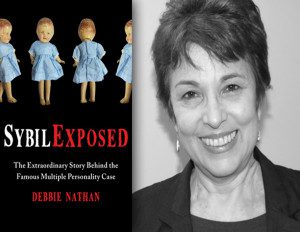

Debbie Nathan, author of Sybil Exposed, wrote a persuasive argument that the 1973 best selling biography of multiple personalities was nothing more than a work of fiction.

Sybil Exposed

by Elisa Forsgren

May 2, 2012

A journalist is a nonfiction writer. A nonfiction writer has a responsibility to provide her readers with the absolute truth. Readers invest a certain amount of trust to a nonfiction writer. Journalist Flora Schreiber apparently found no obligation or veracity due to more than six million people who purchased her 1973 biography of Sybil, an American woman with 16 personalities. Sybil’s psychiatrist introduced multiple personality disorder as an official diagnosis that led to important results for the medical profession, the insurance industry and patients. While Sybil remains in print decades after its initial publication, journalist Debbie Nathan wrote a persuasive argument with Sybil Exposed that Sybil was conspired by not only the patient, but even perpetuated by the psychoanalyst and the author hungry for fame and fortune.

All three women involved with the creation of Sybil were long dead by the time Nathan stumbled onto Sybil’s real name. The name Sybil Dorset was used to protect Shirley Mason’s real identity. Years after reading Sybil for the first time, Nathan learned the author’s papers were archived at nearby John Jay College and open for public inspection. Upon inspection Nathan was surprised to find the papers revealed that Sybil’s 16 personalities had not just appeared rather they were the direct result of years of rogue intensive drug treatment that violated every ethical standard of practice for mental health practitioners.

Along with the archives, Nathan used the census and other historical records to reconstruct the childhoods, young adulthoods, and experiences as professional women in the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, and beyond. She successfully tracked down relatives, friends, and colleagues who were still alive. She interviewed people by phone and traveled North America to meet in person and compared the archival material to her discoveries outside of the library that would yield new insight and inquiries. Through her extensive research Nathan found that “Sybil was as much about the conflict between women’s highest hopes and deepest fears as it was about a medical diagnosis.” Nathan “suspected that the frustrations they’d endured as ambitious women in a pre-feminist age, and the struggles they’d mounted regardless, had infused the Sybil story with a weird yet potent appeal for women.”

Mason grew up in a small Minnesota town, the only child of strict Seventh-Day Adventists. She always needed attention and as an only child, and often she received all the attention of her parents, although not always positive. She suffered from physical and emotional illnesses along with OCD tendencies. Mason began treatment in 1945 for five sessions but the therapy was discontinued when her doctor looked for a new job out of state. The two parted ways and Mason actually did well in the nine years she was on her own but her past symptoms returned after moving to New York city in 1954 to attend Columbia Teacher’s College. Dr. Cornelia B. Wilbur, now a Manhattan psychoanalyst, was found again by Mason who booked an appointment hoping for the same positive results.

As a child, Wilbur, smart and charismatic, was hurt by her father’s declaration that she did not possess the intelligence to become a doctor. Still she yearned and longed to be somebody important. And here was Mason, the perfect patient, eager to please her psychiatrist at any cost. Wilbur prescribed Mason a variety of highly addictive drugs: Seconal, Demerol, Edrisal and Daprisal, including several that have now been discredited. One drug, Pentathol, known at the time as a truth serum, is now believed to encourage patients to describe fantasies or experiences that could have never happened. Mason knew her time with the doctor was running out and even though She longed to see more of Wilbur, therapy would soon cease for this garden-variety neurotic. Wilbur had provided all that she could do to help Mason, who developed a romantic crush on her doctor. Mason feared once therapy ended, she would no longer see Wilbur. According to Nathan’s research, Mason’s desires to continue therapy with Wilbur were so great that she fabricated her first personality in order to remain in her care. So one day, Mason showed up for an appointment as Peggy. The following week Wilbur was introduced to Vicky in Mason’s body. Followed by a whole slew of personalities, ironically with the same name Mason had for her childhood dolls as Nathan’s research showed. After these pivotal sessions Wilbur suggested that her patient become the subject of a book.

It was a win-win for both women. Wilbur had found a way to make her mark as a successful doctor with Mason diagnosed as a multiple personality. Mason was relieved to have her condition and now abundant attention from the good doctor she unconditionally loved. Wilbur vowed to cure her patient no matter how much time it took. She would do it in her office, because Mason deserved personalized, loving care, not warehousing in a crowded mental hospital. Wilbur devoted more time, exactly what Mason wanted to achieve.

Nathan found Wilbur had approached Mason’s health problems with a predetermined diagnosis using therapy with extravagant, sadistic use of habit-forming, mind-bending drugs. Wilbur would treat the patient day and night, on weekdays and weekends, inside her office and outside, making house calls and even taking Mason with her to social events and on vacations. She fed Mason, gave her money and paid her rent. After years of this behavior, the according to Nathan, “the two women developed a slavish mutual dependency upon each other.”

Nathan revealed that Wilbur had always thought that she was helping her female patients despite the self-indulgent motives. Wilbur unfailingly pushed them to follow their dream, even though the therapy she used on them was bizarre and required that they become multiple personalities in order to receive her care. Wilbur saw herself as a nurturer, a maternal figure, a modern mother, just what Mason needed from her doctor.

Wilbur needed for her reputation to be fully established by describing her success working with Mason’s MPD case in a book she asked Schreiber to write. Schreiber was a self-aggrandizing spinster who specialized in trashy, made-up, “real-life” women’s magazine stories. Schreiber agreed to author only if the story had a cure for only a happy ending would sell a MPD book. Wilbur guaranteed after a year of therapy Mason would be cured. Mason was told the book proceeds would repay the $30,000 she owed Wilbur in therapy fees. A year passed and Wilbur told Mason “she would simply have to get well” because the book and their friendship depended on it. Ever-willing to her beloved doctor, Mason obliged, faked a seizure and the other personalities never reappeared again.

Schreiber began research on Mason’s life and case history in 1965. Nathan wrote, “very quickly… she discovered problems with the story, problems so profound that she would wonder if she could write a book about Shirley [Mason],” when Schreiber found and read Mason’s five page letter confessing the complete fabrication of all the personalities. Schreiber was sick with the idea the alters were actually a big lie and she was tempted to trash the project. However Schreiber told her friends, colleagues, and all the famous psychiatrists that she was writing Sybil. The author already accepted and spent an advance on the book and was contractually obligated to finish in five months. Schreiber revealed her doubts to Wilbur, who in turn told her patient. Mason insisted to Schreiber she had multiple personalities and she had solid evidence: her high school and college journals, which she then provided to Schreiber. Remarkably the sudden appearance of this solid proof did not tip off the seasoned journalist and yet if Schreiber had used the due diligence of a true investigative reporter, she would have noted the 1941 journals were written in ballpoint pen, which was not in the U.S. until 1945. The journals were fake.

The deceit worked. Schreiber wrote the book and despite her embellished additions she adamantly defended that as a whole, the story was emotionally true regardless of the confusing and even patently false case history details. Schreiber perceived the heroine of her book as the woman in flux. She also struggled to do transformative work during a time of women’s suffrage and change. Sybil was her brass ring, a chance to do serious work of nonfiction and rather than expose Wilbur and Mason when she found the personalities to be fraudulent, Schreiber also contributed to the made-up facts.

Nathan uncovered that if Wilbur were not in the picture Mason still would have struggled in life. Perhaps she would have expressed her feelings into art that could have reached a professional stature rather than languishing years in psychotherapy. The young woman who became Sybil, fell in with a psychiatrist and a journalist, who both voluntarily hitched themselves to what they all knew was a lie and together the three saw their project, a revolutionary book about female mental suffering. They became Sybil Incorporated that made money for a while. The book and medical case changed the course of psychiatry but each individual paid their own price for their sins. Mason had to give up her friends and become a recluse. Schreiber lost control of her success and ran through her fortune and reputation. Wilbur used her medical credentials to aggressively promote a diagnosis that ultimately hurt women far more than it helped them and defined their conflicts as pathological and curable.

Though the three women shared in the canard, each had different reasons for maintaining and even adding to the charade. Mason feared losing Wilbur yet when she wrote a five-page confession letter admitting to the farce, the doctor treated the letter as a “metaphor” that showed Mason’s progress. Wilbur would not accept a recantation of her diagnosis of MPD or the most important patient of her career, not to mention of medical history. Mason’s case catapulted Wilbur into the notoriety she desired, she was rubbing elbows with important people and asked to speak at conferences. Wilbur knew this would be a groundbreaking experiment and understanding the disorder would establish her as one of the greatest professionals in her field.

When Sybil was published, Nathan argues that it was either a case of gross negligence on the part of Mason, Wilbur, and Schreiber or fraud. In addition to the diary collaboration with Mason, Wilbur withheld from Schreiber the knowledge that Mason suffered from pernicious anemia, a condition that may cause hallucinations, depression, anxiety, aching, weight loss, and confusion about identity, which were also many of Mason’s lifelong symptoms. Nathan handles her conjecture of the archived materials with great care to not force conclusions, such as a possible sexual relationship between doctor and patient, where the evidence is not available. Nathan narrates a well-argued case of how Wilbur completely failed her patient, how a doctor and journalist carried out professional fraud, unethical practices and negligence, and more remarkably how one modest young woman spun a little fib for attention into a diagnosis that turned psychiatry on its head and radically changed the course of therapy and culture.

In an interview found online, Nathan said that each woman was “in her own way brilliant, ambitious, damaged by the sexism of her time –and ruthless. Each was fractured.” She is clearly fascinated by the three women and what they did, but she also asks why the public “acceded so easily, so effervescently… what was going on in the 1970s that made us so grossly negligent of our common sense? Why did we want to believe a story as over the top as Sybil?” Nathan answers in the Epilogue. “The Sybil craze erupted during a splintered moment in history, when women pushed to go forward and the culture pulled back in fear. Sybil, with her brilliant and traumatized multiplicity, became a language of our conflict, our idiom of distress.” There was the “headiness and equality of women’s liberation” but also the weight and pull of tradition. Women, who bought the book far more than men, resonated to the idea that stress could fracture the mind. All this made it possible for Mason, Wilbur, and Schreiber to concoct one of the largest, most shocking cases of deception in the twentieth century.

###

Sources:

Nathan, Debbie. Sybil Exposed: the Extraordinary Story Behind the Famous

Multiple Personality Case. 1st Free Press hardcover ed. New York: Free,

- Print.

Smith, Kyle. “’sybil’ Is One Big Psych-Out.” New York Post. N.p., 15 Oct. 2011. Web. 11 Apr. 2012. <http://www.nypost.com/p/news/local/sybil_is_one_big_psych_out_NaIEczKkVakx8ZLLi7GQPI#ixzz1bA3UiApO>.

Neary, Lynn. “Real Sybil Admits Multiple Personalities Were Fake.” NPR.com. N.p., Oct. 2011. Web. 9 Apr. 2012. <http://www.npr.org/2011/10/20/141514464/real-sybil-admits-multiple-personalities-were-fake>.

Bosch, Torie. “Sybil Exposed by Debbie Nathan the Double x Book of the Week.” X Factor What Women Really Think. N.p., 11 Nov. 2011. Web. 9 Apr. 2012. <http://www.slate.com/blogs/xx_factor/2011/11/11/sybil_exposed_by_debbie_nathan_the_doublex_book_of_the_week_.html>.