Every morning an hour before sunrise, Ace turns off his alarm and makes a pot of coffee. He washes from a pail of rainwater he has collected. He holds a shirt up to his nose and inhales deeply.

“It’s clean,” he says with a bright smile.

Ace runs down a path to catch a 5:20 a.m. bus to East Bay where he begins his 12 to 15 hour workday at one of his three jobs. In the afternoon he takes another bus to Alameda where he cares for a disabled homebound veteran. When he is relieved from home care duties, he works as a night watchman every other evening. After a long hard day Ace can’t wait to get home again. But for Ace, home is a tent.

“It’s gonna be a long day tomorrow,” he says and with a wink adds, “But worth it.”

Ace has a rather unique living situation in a tent, with a sleeping bag for a bed and a hope for a better tomorrow.

This time tomorrow is different. Tomorrow Ace signs a lease on his own apartment, a goal that has taken him three years to reach.

“It’s real hard,” Ace says. “Especially at my age.”

Ace just turned 50 when his girlfriend of five years cleaned out his bank account and took off with another man.

“I hit what I thought was bottom,” he says.

Ace didn’t handle the split well and took his troubles to the bar.

“I got so loaded, I missed work for four days and I guess the office didn’t like that because they fired me,” Ace says.

Ace slipped into depression and started drinking more as a means of self-medication to deaden the pain he felt from his heartbreak. Soon days turned into weeks that turned into months. His car was repossessed. The utilities shut off in his home. One day he came home to find he was locked out. A huge notice on the door, he had been evicted. All of his possessions were taken out to the street early in the morning and by the time he arrived home, there was hardly anything left but a few articles of clothing and a couple of personal items.

“At least I’ve got this,” Ace says pointing to a photo album – the only remains to show of the life he once lived.

Ace grew up in San Rafael, went to San Rafael High School and later graduated from University of California, Berkeley with honors. Though he traveled the world, he found nothing as beautiful as the Bay Area and bought a house off Jewel Street in San Rafael.

“I knew I wanted to live the rest of my life here,” Ace says.

Ace sunk into a deep depression after his girlfriend left. He didn’t answer the door, pick up the phone or open the mail for almost a full year. He had no idea he was on the verge of losing everything.

“But I really didn’t lose everything,” Ace says pointing to his head. “I’ve still got my mind, sharp as a tack.”

When Ace found himself suddenly without a home he finally touched bottom and realized too late this new life as homeless wasn’t for him. He had no idea where to go and what to do. He needed a place to stay, it was November and it was cold.

“I spent that first night just walking around thinking, feeling sorry for myself and then it dawned on me: I did this,” Ace says. “And if I did this to myself, I can un-do it and get myself out.”

But getting back up is not as easy as going down. Once he was without a home he was treated differently.

“Everyone judges you as a bad person, I’ve made some poor choices in my life, but I’m not a bad person,” he says.

Ace decided he had to turn his life around but first he was hungry. While he wandered through downtown San Rafael streets, he found a free warm lunch served at St. Vincent de Paul on B Street where he met people in the same housing predicament.

“I remember when Ace first walked in, he was alone, bewildered and confused,” Robert Singler the dining room manager says. “But at least he found his way in here and he left with a full stomach and bunch of new friends who understood his frustration.”

Steve Boyer, executive director of the St. Vincent de Paul Society of Marin, who noted hot lunches served at the agency’s San Rafael dining hall remain high — an average of 325 meals daily and climbing, up from an average 243 daily in 2011. Last year, the society helped more than 16,000 people in the community, offering assistance in the form of free hot meals, rental deposits, utility assistance, social service referrals, and other vital needs.

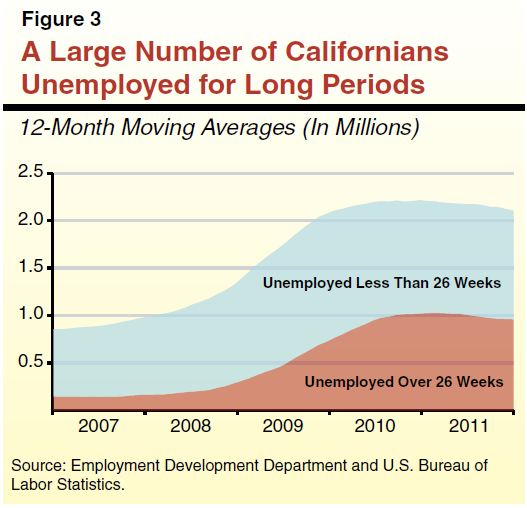

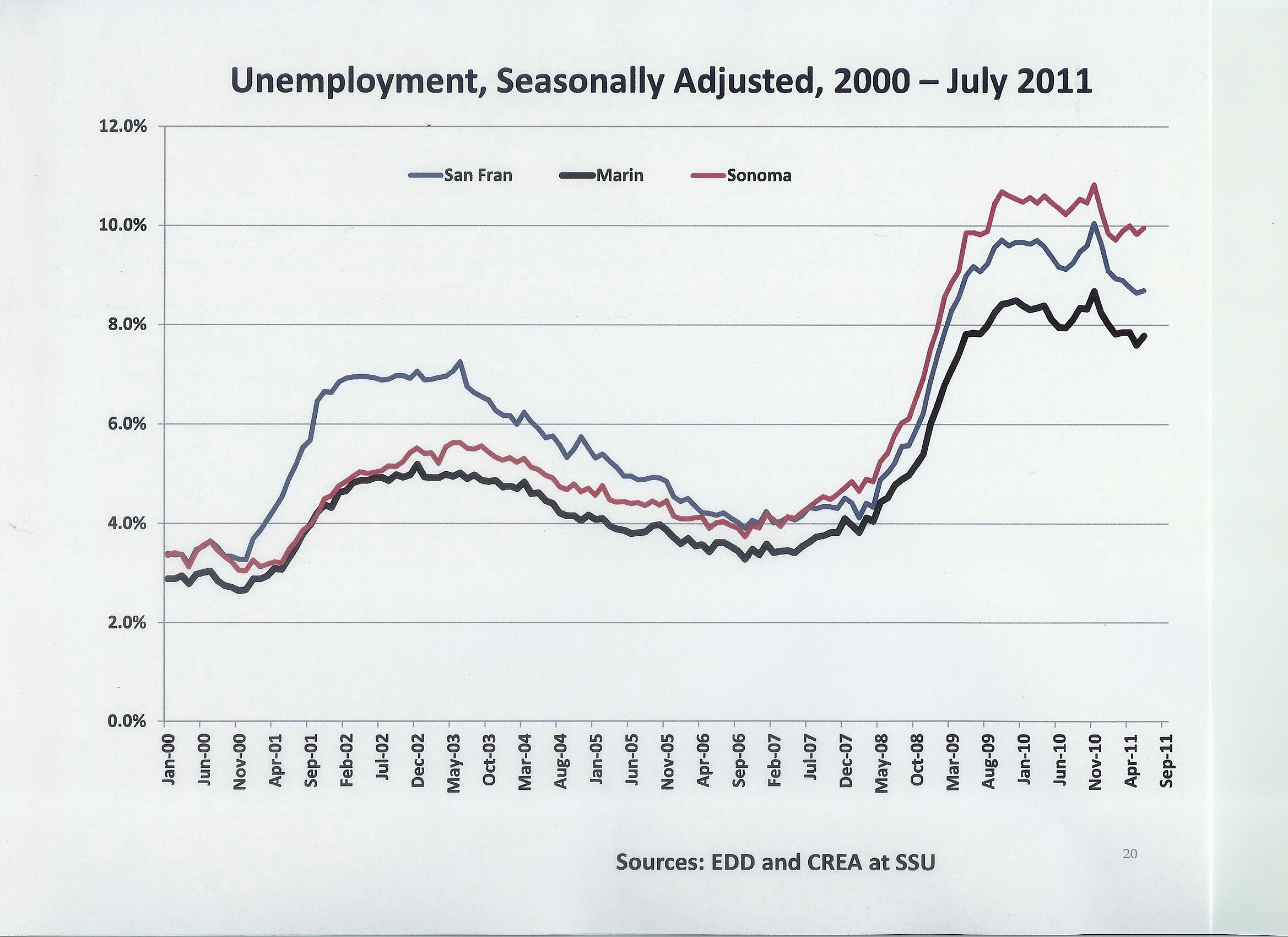

“We haven’t seen a recovery in the economy from our perspective,” Boyer said, adding that the county’s jobless situation “hasn’t impacted the people we serve at all.

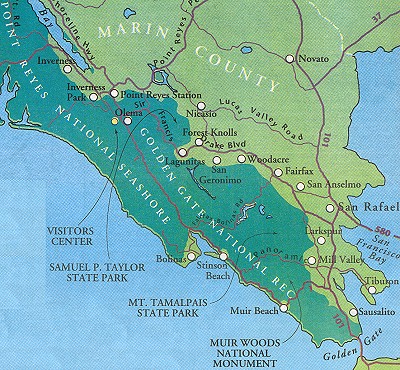

Many of the friends Ace made were also homeless who would rely on friends and family to keep them off the streets. Others played a daily game of housing roulette or finding a bed available in very limited shelter space. The county is 85 percent open space and many camp in the hills surrounding San Rafael and Mount Tamalpais. Some sleep in parks while others live in their cars and an adventurous few anchor out in Richardson Bay off Sausalito.

“Sleeping on a boat is not as glamorous as it sounds, often it was one of the only ways to stay safe,” Ace says.

In his three years spent homeless, Ace found living in a tent alone secluded far up in the hills was the safest way to live. Many nights he wouldn’t sleep for fear he would be beaten in his sleep or even killed for being without a door and lock for protection.

“I learned to not stand out and made myself real busy working and saving so I could get back on my feet again,” Ace says.

While Ace was able to find work, other people without a home didn’t have such an easy time finding jobs available to them.

“I was able to use the phone and mailbox at Ritter Center,” Ace says. The center gave him a leg up towards obtaining work quickly.

The Ritter Center in San Rafael, helps handle a workload of 3,700 impoverished, homeless, jobless or otherwise out-of-luck clients who depend on the center for a helping hand with clothing, food, employment, housing, laundry and related services.

“People are either losing their jobs or having their hours cut back and need our services,” says Ben Leroi deputy director of the center.

Homelessness is not a new phenomenon to the U.S., California or even a small city like San Rafael. Since the colonial times, homeless people have been present in America. Despite its image as an affluent enclave, Marin is not immune to the persistent problem of homeless residents and since San Rafael is the county seat with an urban setting, it’s not surprising to find a lion’s share of the population according to Leroi.

“Most of our clients are from Marin and grew up here in San Rafael,” Leroi says.

Based on the most recent one-day count taken by the county, the estimated homeless falls somewhere between 1,770 and 6,000 where at least 1,500 are children Marin school officials say.

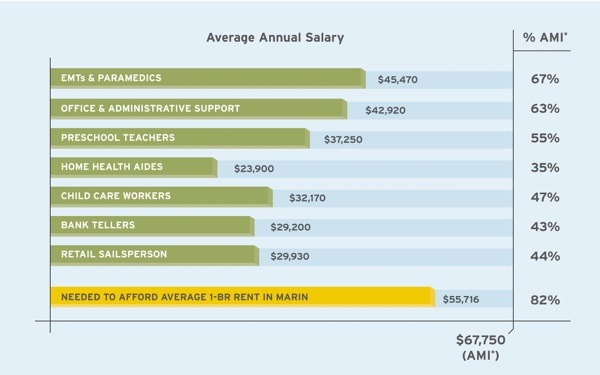

The problem in Marin is compounded by overpriced housing and land costs along with the lack of low-income housing. People that fill the jobs of the services that are provided in Marin do not get paid enough to live and work in Marin according to Leroi.

According to the Marin Department of Health and Human Services, the income required for a family of three to attain self-sufficiency is $68,800 annually.

“For those without a job, it remains a stark world indeed,” agreed Thomas Peters, CEO of the Marin Community Foundation. “That’s why the foundation is redoubling its efforts to support individuals and local agencies seeking to close the gap between available jobs and marketable skills.”

“Poverty and homeless are closely linked. There are many reasons why a family or individual like Ace become homeless. However, the primary contribution to homelessness is affordable housing,” says Larry Meredith, director of Marin Department of Health and Human Services.

According to American Community Survey Census data 6.4 percent of Marin’s population was estimated to live below 100 percent of the Federal Poverty Level.

“When households lack income to provide for basic needs, they are forced to choose between housing costs, childcare, healthcare and food. Many households don’t make enough to provide for housing stability,” Meredith says.

“You must earn over $35 an hour full-time to afford an average two bedroom apartment in San Rafael,” Leroi says.

A few weeks ago, Ace turned 54 and finally reached his goal: he managed to save up enough money to put down a deposit and pay six months of rent in advance.

“It’s real hard to depend on the kindness of strangers,” Ace says. “Humbling. Real hard and oh-so-humbling.”

Tomorrow night will be the first time in three years in his own bed, in his own place with a real roof over his head.

“I won’t go back to the homeless life again. It’s a cycle that sucks you in like a deadly whirlpool, I’m just glad I didn’t drown,” Ace says.

###

-

The vast open space of Marin County provides the perfect area to set up camp and live rather than on the streets. But even in this beautiful scene danger lurks with fires, other aggressive homeless and court ordered evictions by the police.

-

Tent living can be done, but as for Ace, he is not made for this life.

-

-

The photo album that Ace managed to salvage after his eviction serves as the only reminder of a life he once lived and so desperately desired to get back.

-

San Rafael High School where Ace attended.

-

A house on Jewel Street similar to the house Ace owned before he was forced onto the streets.

-

The main drag, Fourth Street , San Rafael, CA.

-

Areal view of San Rafael, CA.

-

St. Vincent de Paul dining room on B Street in San Rafael, CA where Ace found food and friends.

-

Friends of Ace provide comfort to each other outside of St. Vincent de Paul Society.

-

Very limited sleeping arrangements in the shelters force many to seek other alternatives for the night.

-

-

-

Boats in Richardson Bay where many homeless will seek shelter from the cruel streets.

-

Boats in Richardson Bay, CA serve as another rest spot for many of the county's growing homeless population.

-

Clients of Ritter Center in San Rafael gathered Nov. 26, 2013 outside the center to receive frozen turkeys and bags of grocery goodies as part of the center's Thanksgiving holiday giveaway. (Megan Hansen/Marin Independent Journal)

-

Marin Department of Health and Human Services

-

Marin Community Foundation

-

Overview map of the Open Space in Marin County, CA.

-

The growing population of people without homes is daunting in San Rafael, CA as these fellows lead a rally in honor of their friends who have died living on the street.

-

Two homeless men discuss their plans for the day in San Rafael, CA.