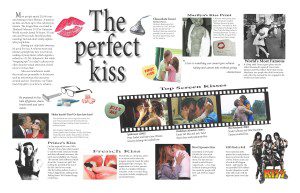

Part of a package spread for Valentine’s Day, including a piece like the piece below for online.

The Rice Irwin Kiss vs. Jaco Van Dormael

A kiss is when the lips touch with the lips or other body parts of another person or object. This simple act can convey a wide range of emotions depending on the cultural connotations and context. Ernest Crawley, an anthropological writer, who studied the origins of the kiss in the early 20th century, said a kiss was “a universal expression in the social life of the higher civilizations of the feelings of affection, love and veneration.”[1] The culture, relationship and context interpret the different social significance of the gesture. Compare the short 1896 film The Rice/Irwin Kiss directed by William Heise to Kiss directed by Jaco Van Dormael in 1995. While the kiss performed in these two films appears to be similar, the analysis of film form, mise-en-scene and cinematography actually show they are very different.

A film’s explicit or implicit meaning bear the social values or symptomatic meaning and reveals a social ideology.[2] The invention of the Vitascope provided the first public theatrical exhibition of film and also the first onscreen kiss. The performance by May Irwin and John Rice in 1896 was a re-enactment of a scene in the Broadway musical, “The Widow Jones” made specifically for the Vitascope. The kiss lasts less than a minute, yet in the society at that time, the film was met with severe disapproval by defenders of public morality. This clearly shows how a work can disturb our normal expectations gathered from our culture. in 1896 American society, a kiss was an intimate act performed in private therefore Heise disturbed the expectation, which left some viewers disoriented and unable to engage in the film’s form.

In comparison, the Lumiere brothers invented a multifunctional device that served as a camera, film processor and projector, patented in 1895 as the Cinematographe. In honor of the 100th anniversary, 40 directors around the world were invited to use the device to create a short film with no synchronous sound, 52-second duration and only three takes. Jaco Van Dormael, a Belgian film director, known for the respectful and sympathetic portrayal of mental and physical disabilities, rose to the challenge. At the time, Dormael was in production on a film, The Eighth Day (Dormael, 1996), with actors who have Down syndrome, who also appear in his 52-second short film Kiss (1995). While the use of actors with visible disabilities is outside the normative paradigm, the film is not found to be disturbing but rather sweet and endearing to most viewers.

Another area of comparison, mise-en-scene, used to achieve realism, gives the setting an authentic look or letting actors perform as naturally as possible.[3] The setting for Rice/Irwin Kiss is a black backdrop with no other movement to distract from the two actors while Van Dormael placed his actors in front of a light-colored public building that operated as both a way to highlight his actors and to emphasize placement. The people in the background provide additional movement within the shot and the setting dynamically enters the narrative action. Our tendency to notice visual difference is strongly aroused when the image includes movement.[4] The lighter and darker areas with the frame help create the overall composition of each shot and guide our attention to certain objects and actions. The blown-out brightly illuminated clothing of the woman in the Rice/Irwin Kiss draws the eye to a key gesture, while a shadows articulate textures: the curve of a face, the twist of the mustache and the grasp of a hand.

The action of Rice/Irwin Kiss appears as though the actors are having a conversation more than in the act of a kiss. Both heads are held together and almost nuzzle each other affectionately until the climatic end when the man in a grand gesture leans back twists the ends of his mustache and they both lean in for the kiss at which time the man presses his hands on the woman’s cheeks to draw her in deep and close. Van Dormael has the actors break the fourth wall and look directly into the camera with a slight smile, then turn and face each other with a smile they lean in and gently kiss. The initial kiss stops and only the top of their foreheads touch, eyes closed as if to savor the moment, each lost in a dreamy smile of passion. Then she begins to nuzzle him and rests her head on his shoulder, returns her lips to his and the kiss becomes more passionate, involving both to use hands and arms freely to caress the other. While both films contribute to only the visual aspects the acting style of Van Dormael seemed natural and spontaneous.

Rice/Irwin Kiss distributes various points of interest evenly around the frame in bilateral symmetry while Van Dormael’s male actor dominates the screen and the female is only in one fourth of the frame. The higher-contrast of Rice/Irwin Kiss seems to strive for a middle range of contrast that consists of pure blacks, pure whites, and a large range in between grays. Whereas Van Dormael’s use of lower-contrast displays many intermediate grays with no true white or black areas. Still our attention is guided by the use of contrast. Light costumes and brightly lit faces stand out while darker areas tend to recede as in the black background of Rice/Irwin Kiss. But in Van Dormael short film the use of a light background predominantly displays the dark elements such as the hair color of both actors. The high contrast images can seem stark and dramatic, while low-contrast ones suggest more muted emotional states.[5]

Despite the changes in our culture over 100 years, The Rice/Irwin Kiss continues to agitate the viewer’s expectations due mostly to the attractiveness of the couple whereas Van Dormael’s Kiss using two Down syndrome actors summons a sweet sincerity that allows the viewer to accept the action as normal. The mise-en-scene limited to the actors in The Rice/Irwin Kiss punctuates the performance while Van Dormael’s setting adds an element of distraction. The high-contrast of The Rice/Irwin Kiss lends to the drama while the low-contrast of Van Dormael’s portrays a softer emotion. Upon first view both films seem to be very similar: a man and woman embraced in a kiss filmed in black and white but with particular attention given to the form, mise-en-scene and cinematography, the complex diversity of each film is shown.

[1] Crawley, Ernest. Studies of Savages and Sex, Kessinger Publishing (revised and reprinted) (2006) Crawley, Ernest. Studies of Savages and Sex, Kessinger Publishing (revised and reprinted) (2006)

[2] Bordwell, David. Thompson, Kristin. Film Art: An Introduction, McGraw Hill (2012) p. 60

[3] Bordwell, David. Thompson, Kristin. Film Art: An Introduction, McGraw Hill (2012) p. 112-113

[4] Bordwell, David. Thompson, Kristin. Film Art: An Introduction, McGraw Hill (2012) p. 144

[5] Bordwell, David. Thompson, Kristin. Film Art: An Introduction, McGraw Hill (2012) p. 144

Link May Irwin Kiss: https://youtu.be/Q690-IexNB4

Link Van Dormal Kiss: https://youtu.be/cXz_TNZAVFk